3.4.Accessing Information

\(3.4.\)Accessing Information

1.Machine code properties

x86-64 instructions can range in length from 1 to 15 bytes, it isn't fixed.

The instruction format is designed to insure that there's a unique decoding of the bytes into machine instructions. For example, only

pushq %rbxcan start with53(can be analogied with opcode in RISC-V).The disassembler determines the assembly code based purely on the byte sequences in the machine-code file.

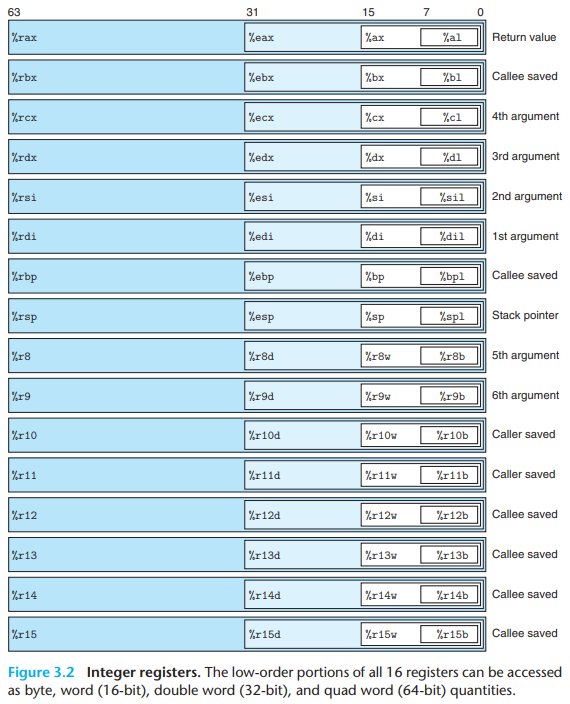

2.Registers

When we present instructions copying and generating 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-byte values, we follow the two conventions:

Those that generate 1- or 2-byte quantities leave the remaining bytes unchanged.

Those that generate 4-byte quantities set the upper 4 bytes of the register to zero.

A function returns a value by storing it in register

%rax, or in one of the low-order portions of this register.

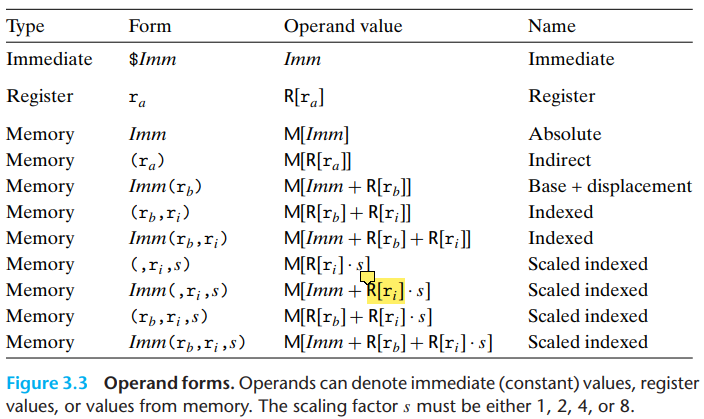

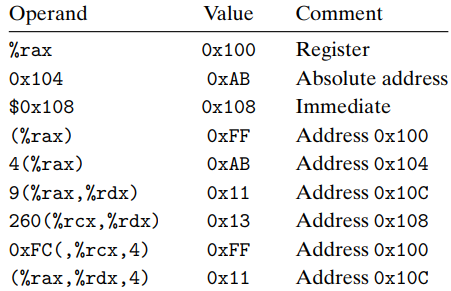

3.Operand specifiers

There are three types of operand possibilities:

Immediate: It refers to constant value. In ATT format assembly code, it is written with a

$along with an integer.Register: It denotes the content of a register. We use the notation \(r_a\) to denote a register \(a\) and indicate its value with \(R{[r_{a}]}\).

Memory: The most general form of it is \(Imm({r_b},{r_i},s)\), which is computed as \(Imm+R[{r_b}]+R[{r_s}] \cdot s\).

- \(Imm\) is the immediate offset, \(r_b\) is the base register, \(r_i\) is the index register.

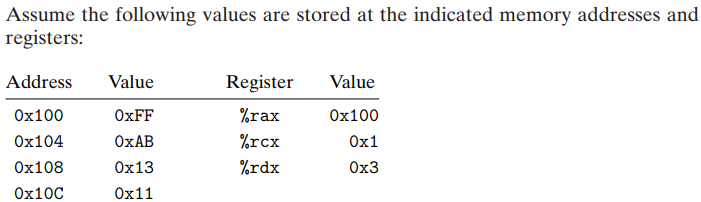

\(e.g.\)

4.Data Movement Instructions

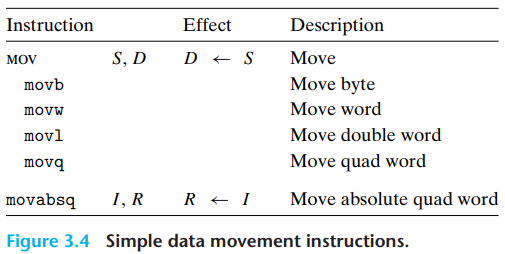

\(a.\)Simple data movement instructions

The source operand designates a value that is immediate, stored in a register, or stored in memory.

The destination operand designates a location that is either a register or a memory address.

The value is first passed from source to a register, then from the register to the destination.

The regular

movqinstruction can only have immediate source operands that can be represented as 32-bit two�s-complement numbers. This value is then sign extended to produce the 64-bit value for the destination. Themovabsqinstruction can have an arbitrary 64-bit immediate value as its source operand and can only have a register as a destination.

In x86-64, any instruction that generates a 32-bit value for a register also sets the high-order portion of the register to 0.

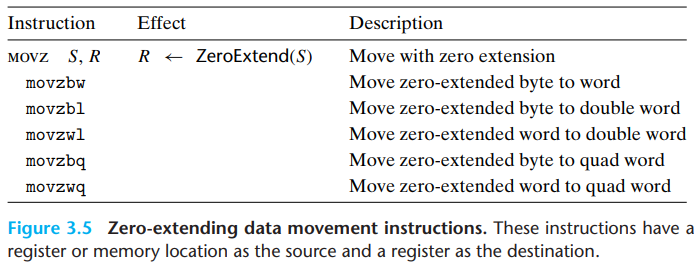

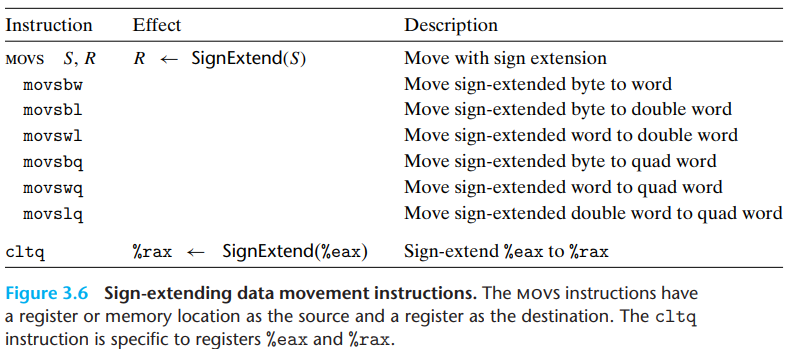

\(b.\)Bit-extending data movement instructions

Each instruction name has size designators as its final two characters�the first specifying the source size, and the second specifying the destination size.

The source can be either a register or stored in memory.

The destination is a register.

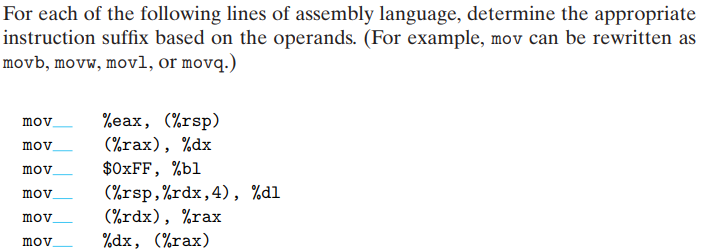

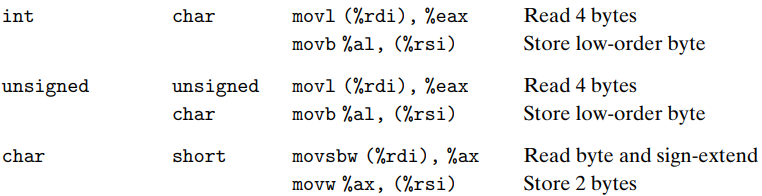

\(e.g.\)(Suffix decision)

\(solution:\)There are several points to note:

In x86-64, we always give quad word registers to memory reference, such as

%rax.We first decide which suffix to use by the destination. For example,

movb $0xFF %bl.If the destination is a memory address(such as

(%rax)), we decide which suffix to use by the source.

Note that if both the source and the destination are from memory, we can use all four suffix. The x86-64 imposes the restriction that a move instruction cannot have both operands refer to memory locations.

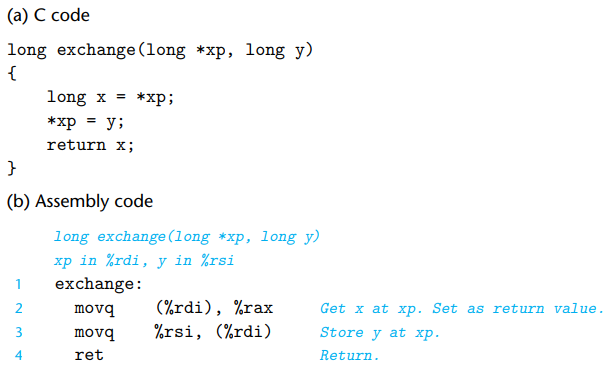

\(c.\)Data movement example

Procedure parameters

xpandyare stored in registers%rdiand%rsi.Dereferencing a pointer involves copying that pointer into a register, and then using this register in a memory reference.

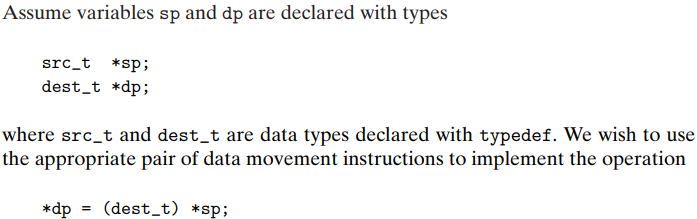

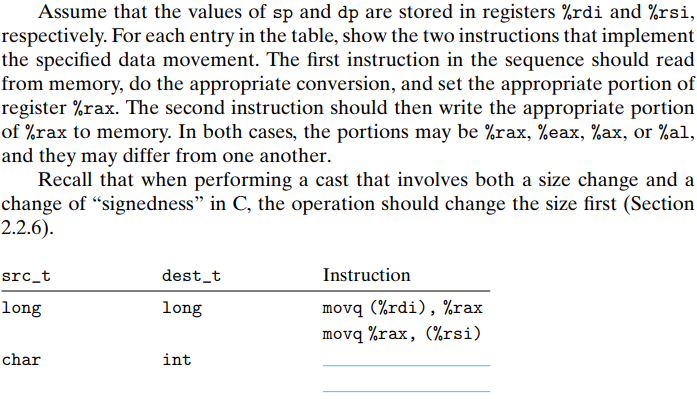

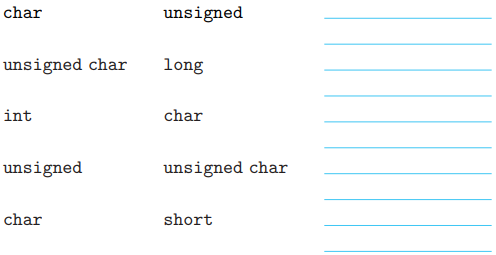

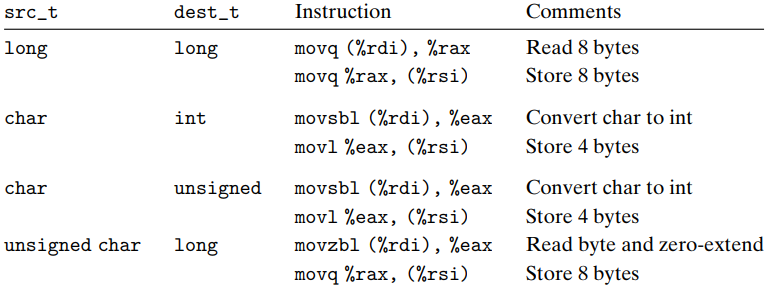

\(e.g.\)(Casting)

\(solution:\)The casting is in

fact the extension of bits. For example, if we want to

convert char to int, because char

takes word bits while int takes 32 bits, we use

movsbl to implement operations

likeint x = (int) char_element:

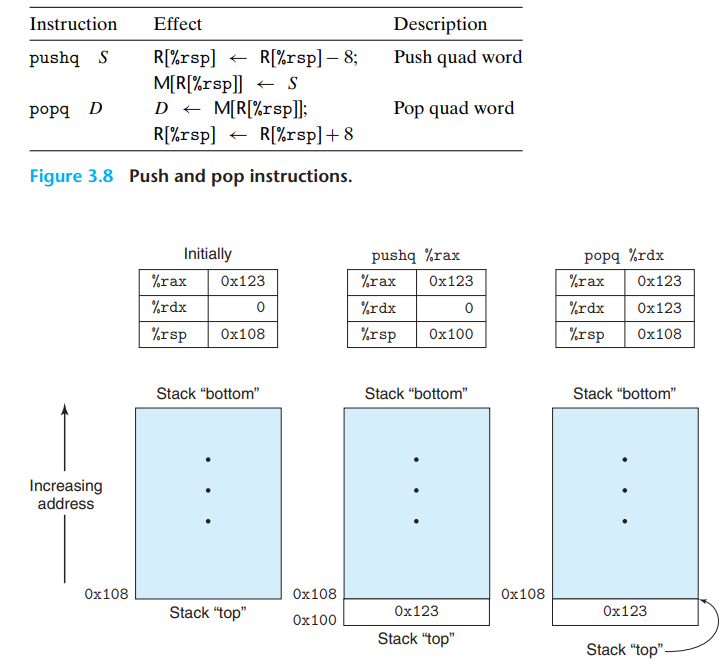

\(d.\)Stack operation