8.5.Signal

\(8.5.\)Signal

1.Signal Terminology

A signal is a small message that notifies a process that an event of some type has occurred in the system.

The transfer of a signal to a destination process contains two distinct steps:

- Sending a signal: The kernel sends a signal to a destination process by updating some state in the context of the destination process.

The signal is delivered for one of two reasons:

The kernel has detected a system event such as a divide-by-zero error or the termination of a child process.

A process has invoked the

killfunction.Receiving a signal: A destination process receives a signal when it is forced by the kernel to react in some way to the delivery of the signal.

- The process can either ignore the signal, terminate, or catch the signal by executing a user-level function called a signal handler.

A signal that has been sent but not yet received is called a pending signal.

At any point in time, there can be at most one pending signal of a particular type. If a process has a pending signal of type \(k\), then any subsequent signals of type \(k\) sent to that process will be ignored and simply discarded.

A process can selectively block the receipt of certain signals. When a signal is blocked, it can be delivered, but the resulting pending signal will not be received until the process unblocks the signal.

For each process, the kernel maintains the set of pending signals in the pending bit vector, and the set of blocked signals in the blocked bit vector.

- The kernel sets bit \(k\) in pending whenever a signal of type \(k\) is delivered and clears bit \(k\) in pending whenever a signal of type \(k\) is received.

2.Sending Signals

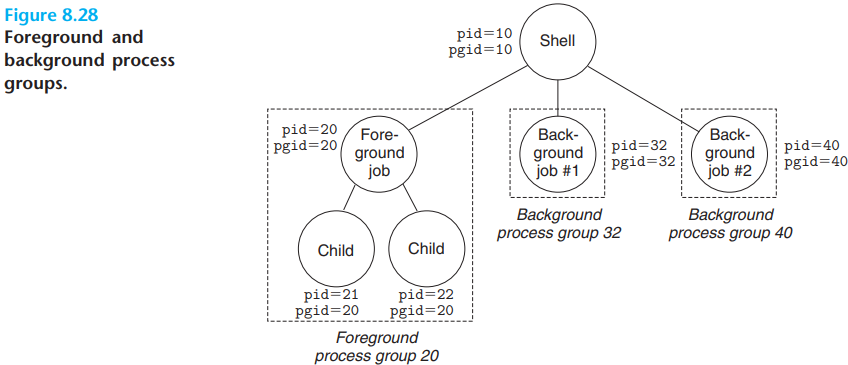

\(a.\)Process groups

Every process belongs to exactly one process group, which is identified by a positive integer process group ID.

The getpgrp function returns the process group ID of the current process.

1 |

|

- By default, a child process belongs to the same process group as its parent.

We can change the process group of a process buyt using the

setpgid function:

1 |

|

If

pidis zero, the PID of the current process is used.If

pgidis zero, the PID of the process specified bypidis used for the process group ID.

\(b.\)Sending signals from the keyboard

Unix shells use the abstraction of a job to represent the processes that are created as a result of evaluating a single command line.

At any point in time, there is at most one foreground job and zero or more background jobs.

\(c.\)Sending signals with the

kill function

Processes send signals to other processes(including

themselves) by calling the kill function:

1 |

|

If

pidis greater than zero, then thekillfunction sends signal numbersigto processpid.If

pidis equal to zero, thenkillsends signalsigto every process in the process group of the calling process, including the calling process itself.If

pidis less than zero, thenkillsends signalsigto every process in process group|pid|(the absolute value ofpid).

\(d.\)Sending signals with the

alarm function

A process can send SIGALRM signals to

itself by calling the alarm function:

1 |

|

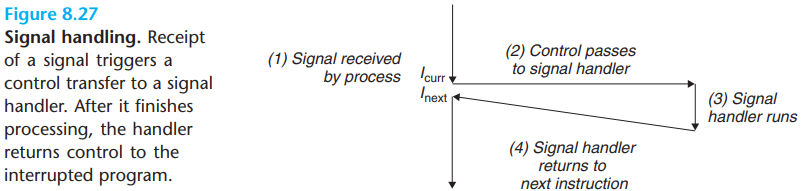

3.Receiving Signals

When the kernel switches a process \(p\) from kernel mode to user mode,

it checks the set of unblocked pending

signals(pending & ~blocked) for \(p\).

If this set is empty, the kernel passes control to the next instruction in the logical control flow of \(p\).

If the set is nonempty, the kernel chooses some signal \(k\) in the set(typically the smallest \(k\)) and forces \(p\) to receive signal \(k\).

- Once the process completes the action, control passes back to the next instruction.

A process can modify the default action associated with a

signal by using the signal function:

1 |

|

The signal function can change the action associated

with a signal signum in one of three ways:

If

handlerisSIG_IGN, then signals of typesignumare ignored.If

handlerisSIG_DFL, then the action for signals of type signum reverts to the default action.Otherwise,

handleris the address of a user-defined function, called a signal handler, that will be called whenever the process receives a signal of typesignum.

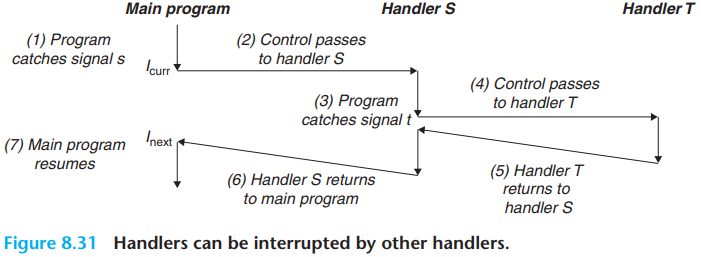

Signal handlers can be interrupted by other handlers:

4.Blocking and Unblocking Signals

Implicit blocking mechanism: By default, the kernel blocks any pending signals of the type currently being processed by a handler.

Explicit blocking mechanism: It can be done by using the

sigprocmaskfunction and its helpers:

1 |

|

The sigprocmask function changes the set of

currently blocked signals. The specific behavior depends on the

value of how:

SIG_BLOCK: Add the signals in set to blocked (blocked = blocked | set).SIG_UNBLOCK: Remove the signals in set from blocked (blocked = blocked & ~set).SIG_SETMASK:blocked = set.

\(a.\)Correct signal handling

Because the pending bit vector contains exactly one bit for each type of signal, there can be at most one pending signal of any particular type. Thus, if two signals of type \(k\) are sent to a destination process while signal \(k\) is blocked because the destination process is currently executing a handler for signal \(k\), then the second signal is simply discarded.

This characteristic of signal handling may lead to some mistakes. Consider the following program, for example:

1 | /* WARNING: This code is buggy! */ |

When executing, we get the following result:

1 | linux> ./signal1 |

We first do some analysis for the program:

The parent process first create three child processes through invoking

Fork().For each child, they will do the conditional

exit(0), terminate and send the signal.The handler fetch the signal, reap the corresponding child process, and send the message.

The result, however, shows that only two child processes are reaped. The reason is that:

Our handler handle one signal per time.

While the handler is still processing the first signal, the second signal is delivered and added to the set of pending signals.

Since the first

SIGCHLDsignals are blocked by the handler, the second signals are not received.While the handler is still processing the first signal, the third signal arrives. Since there is already a pending

SIGCHLD, this thirdSIGCHLDsignal is discarded, and the information of the third signal has been lost.

To fix the problem, we must modify the SIGCHLD handler

to reap as many zombie children as possible each time it is invoked. We

do this by using the while loop:

1 | void handler2(int sig) |

\(b.\)Portable signal handling

The standard sigaction function for specifying the

signal-handling semantics they want when they install a handler is as

below:

1 |

|

The Signal wrapper is as below:

1 | handler_t *Signal(int signum, handler_t *handler) { |

5.Blocking Signals to Avoid Concurrency Bugs

Take the following program as an example:

1 | /* WARNING: This code is buggy! */ |

There consists two concurrent procedure:

The

addjobanddeletejobof the Unix shell job list.The reaping of the child process.

and we may meet the situation that the child process has been

reaped, and the deletejob function tries to delete it,

which is nonexisted.

To prevent this, we blocking SIGCHLD signals

before the call to fork and then unblocking them

only after we have called addjob:

1 | while (1) { |

Notice that children inherit the blocked set of their parents, so we must be careful to unblock the SIGCHLD signal in the child.

6.Explicitly Waiting for Signals

In the previous code, we use while(1) loop to stall

the process. This is wasteful of processor resourses. We can use

sigsuspend instead:

1 |

|

The sigsuspend function temporarily replaces the current blocked set with mask and then suspends the process until the receipt of a signal whose action is either to run a handler or to terminate the process.

This code is equal to the atomic version of the following:

1 | sigprocmask(SIG_BLOCK, &mask, &prev); |